Thanks to colleague Paul Chapman for this article from Mercer ‘Health Wealth Career’. Its looks at the 10 lessons learnt from the GFC and 3 thoughts from what we might expect in the future.

Lesson 1 – Credit cycles are inevitable. As long banks are driven by growth and profit margins their decision-making inevitably leads to greater risk and poorer quality. The growth from 2005-2008 was generated by leverage.

Lesson 2 – The financial system is based on confidence, not numbers. Once confidence in the banking system takes a hit investors start to pull their money out – Northern Rock in the UK.

Lesson 3 – Managing and controlling risk is a nearly impossible task. Managing risk was very difficult with the complexity of the financial instruments – alphabet soup of CDO, CDS, MBS etc. A lot of decisions here were driven by algorithms which even banks couldn’t control at the time. Models include ‘unkown unkowns’

Lesson 4 – Don’t Panic. Politicians learnt from previous crashes not to panic and provided emergency funding for banks, extraordinary cuts in interest rates and the injection of massive amounts of liquidity into the system. The “person on the street” may well not have been aware how close the financial system came to widespread collapse

Lesson 5 – Some banks are too big to be allowed to fail. This principle was established explicitly as a reaction to the crisis. The pure capitalist system rewards risk but failure can lead to bankruptcy and liquidation. The banks had the best of both worlds – reward was privatised with profits but failure was socialised with bailouts from the government. Therefore risk was encouraged.

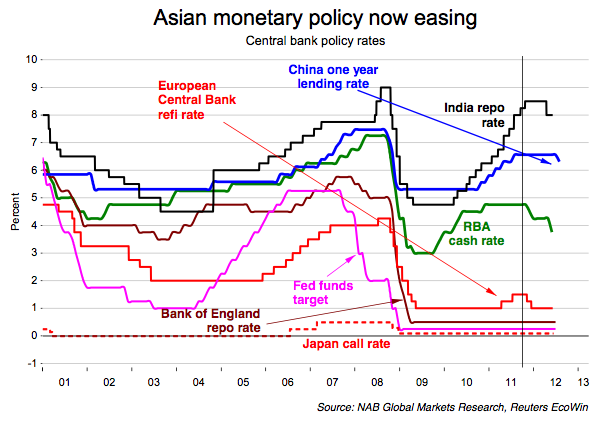

Lesson 6 – Emergency and extraordinary policies work! The rapid move to record low policy interest rates, the injection into the banking system of huge amounts of liquidity and the start of the massive program of asset purchases (quantitative easing or “QE”) were effective at avoiding a deep recession — so, on that basis, the policymakers got it right.

Lesson 7: If massive amounts of liquidity are pumped into the financial system, asset prices will surely rise (even when the action is in the essentially good cause of staving off systemic collapse). They must rise, because the liquidity has to go somewhere, and that somewhere inevitably means some sort of asset.

Lesson 8: If short-term rates are kept at extraordinarily low levels for a long period of time, yields on other assets will eventually fall in sympathy — Yields across asset classes have fallen generally, particularly bond yields. Negative real rates (that is, short-term rates below the rate of inflation) are one of the mechanisms by which the mountain of debt resulting from the GFC is eroded, as the interest accumulated is more than offset by inflation reducing the real value of the debt.

Lesson 9: Extraordinary and untried policies have unexpected outcomes. Against almost all expectations, these extraordinary monetary policies have not proved to be inflationary, or at least not inflationary in terms of consumer prices. But they have been inflationary in terms of asset prices.

Lesson 10: The behavior of securities markets does not conform to expectations. Excess liquidity and persistent low rates have boosted market levels but have also generally suppressed market volatility in a way that was not widely expected.

The Future

Are we entering a period similar to the pre-crash period of 2007/2008? There are undoubtedly some likenesses. Debt levels in the private sector are increasing, and the quality of debt is falling; public-sector debt levels remain very high. Thus, there is arguably a material risk in terms of debt levels.

Thought 1: The next crisis will undoubtedly be different from the last – they always are. The world is changing rapidly in many ways (look at climate change, technology and the “#MeToo” movement as just three examples). You only have to read “This Time is Different” by Ken Rogoff and Carmen Rheinhart to appreciate this.

Thought 2: Don’t depend on regulators preventing future crises. Regulators and other decision makers are like generals, very good at fighting the last war (or crisis) — in this case, forcing bank balance sheets to be materially strengthened or building more-diverse credit portfolios — but they are usually much less effective at anticipating and mitigating the efforts of the next.

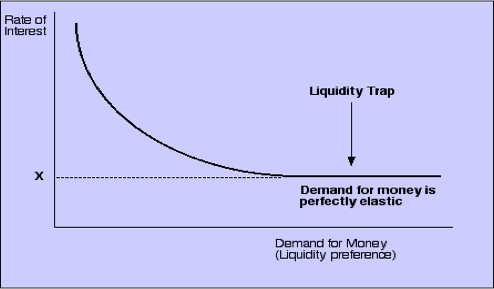

Thought 3: The outlook for monetary policy is unknown. The monetary policy tools used during the financial crisis worked to stave off a deep recession. But we don’t really know how they might work in the future. Record low interest rates with little or no inflation has rendered monetary policy ineffective – a classic liquidity trap.

Source: Mercer – September 2018 – 10 Years after the GFC – 10 lessons